Unpaid Labor

Is creativity reserved for the upper class?

In the wake of my partial unemployment, I’ve given considerable thought to what it means to be an artist. It’s only natural that my thoughts would eventually lead me to just how draining the act of creation can be and, furthermore, what that act of creation perhaps foreshadows for many women later in life.

It requires bravery to initiate the first step in a creative endeavor because it’s scary to be perceived as vulnerable—to be witnessed in a stage of curiosity and exploration that inevitably will lead to some mistakes. That will always be a hurdle for most people. But it’s also scary because of capitalism. Not only are we afraid of making mistakes, we are afraid of the way these mistakes are perceived as failures in the eyes of the money-making machine. American culture loves to remind us that if our endeavors are not producing capital, there is no point.

Sometimes I’ll post a dumb TikTok about a thought that pops into my head, thinking no one will see it, and it ends up being one of my most liked posts.1 Last week, I posted one about my realization that all this thankless and unpaid work I do as a writer and a student is priming me for the thankless and unpaid labor I will do in motherhood should I decide to have children. It sprang from my frustration with school and how it’s felt to work toward a license I won’t have for roughly three years while bringing in next to nothing financially as I watch everyone in my age cohort run circles around me.

I started thinking a lot about the work I do as a creative person. I’m not paid for my writing (this has since changed slightly; I got my eighth paid subscriber this month, so thank you), I was never paid for the music I made, and I rarely, if ever, was paid for photography, unless you count my short stint as a wedding photographer which I absolutely hated. I do these things because I love them, but it also begs the question: how much unpaid and unrecognized work are we willing to do for just ourselves? At what point, if ever, does that stop being worth it? If you were to ask artists like Hilma Af Klint or Vivian Maier, they’d probably say never, a sentiment I mostly agree with. I want to reach that point, and yet I still crave recognition. It’s the perpetual academic in me, always hoping for a gold star, praise, or a head pat to feel validated in my pursuits.

During my undergrad, I had to read Linda Nochlin’s incredible essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? It’s a piece that has reverberated throughout my entire being since I read it all those years ago, and I still think about it regularly. It was one of the first texts written by an art historian I loved and felt riveted by, so it’s lodged within my headspace permanently. I reread Nochlin’s essay recently, which I highly recommend if you haven’t already—there is a full PDF of the text online. In it, she details the plight of women throughout the centuries: how they were required to run households and bear children while their husbands created the next great piece of art or writing, earning immortalized and revered status for centuries to come. Within this narrative, women fell to the wayside, doomed to be secondary characters within their own plot lines and obscured by layers of history while their husbands skyrocketed to fame.

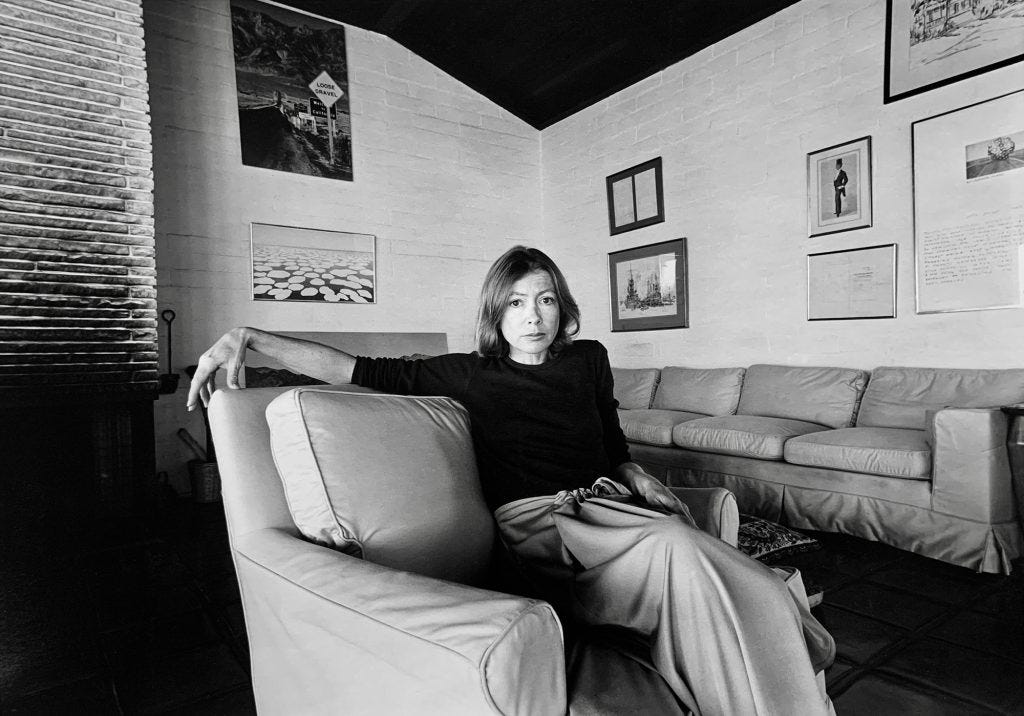

This discourse is also echoed in modern-day context with privilege and race, and Myriam Gurba wrote a searingly accurate essay on the plight of Latinx women as caregivers using Joan Didion as the prime example. And yes—I do want to be Joan Didion, because every literary-adjacent girl who grew up writing in a diary wants to be Joan Didion. But I can acknowledge this want while recognizing her shortcomings as a woman and human being. Petya K. Grady wrote a great piece a few months ago about her disappointment with Didion’s reaction to the women’s movement, which echoes the frustratingly dumb “I’m not a feminist” dialogue thrown around occasionally by some forgettable celebrity. If that sounds bitchy, it’s because I meant it to be. I’m not bitchy often, so I only reserve it for the things that really piss me off. This narrative is old and tired and I’m sick to death of it. While feminism fights for women’s rights, good feminism (i.e. intersectional feminism) fights for everyone's equity. Postmodern feminist theory in psychology critiques systemic barriers and societal context in the therapy room, acknowledging that you cannot separate a person from where they reside within the cultural framework. You can apply this theoretical framework to just about anyone—not just women. This spiel is tangential and I’m getting carried away, but it’s maddening whenever I hear someone engage in this kind of dialogue. It’s like saying, “I don’t see color,” which sounds very ignorant. But I digress.

Without the hired labor of Latinx women, Didion would probably not have been able to write everything she wrote, propelling her into literary royalty. It’s an incredible essay that brilliantly critiques Didion, down to the political repercussions of a poorly placed comma—“brown and lazy” as opposed to “brown, and lazy” while describing her vacation in Guaymas. This subtle shift becomes profoundly politicized in this context.

“Didion’s punctuation succumbs to sloth as she abandons commas to conjure an enduring controlling image: the lazy Mexican.” — Myriam Gurba

The voices we have come to know and love, the voices of great literature and art, are overwhelmingly white and male, and the few female voices who do find their way in were most likely white and from affluent families, which meant they had free time to hone their craft free from the worry of keeping a roof over their heads. They had the time, freedom, and ease necessary to create—and so create they did. This is the crux of Nochlin’s essay, a thesis also echoed in Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. I see this within my own life as I devote myself to school, a new job, my upcoming internship. I have much less capacity for thinking and exploring—both of which stoke the warm fire of creativity.

While we’ve managed to diversify slightly (barely) more, we still face a similar question: why is there such a dearth of art and writing from women of color? Structurally, it’s because the black and brown women who are currently outsourced for the thankless labor of motherhood are too busy taking care of white ladies’ children for a semi-livable wage, then going home and taking care of their own children and husbands free of charge. They have no time to write the next great American novel, not if they want to survive. Not to mention the systemic barriers built on elitism that shut them out, excluding them from the conversation and refusing to give them a seat at the table. Seemingly innocuous critiques of grammar, structure, and language by the literati and art critics are thinly veiled excuses for further racism and prejudice against marginalized communities. Meanwhile, futile attempts at inclusion through the “outsider art” category often paradoxically reinforce the othering it claims to counteract.

The heartbreaking fact is that, even if they wanted to, so many women do not have the time or the resources to make that a reality, and there are many reasons for this. Some do succeed, but they are not set up for success in the same way men are. This difficulty is further compounded for women of color, those who are chronically ill or disabled, and those struggling with poverty. Those who “make it,” are the exception in this world created for and by white, heterosexual, cisgender men—not the rule. We can write essays and think pieces critiquing the glass ceiling and the mental load, but nothing will change if we continue to accept this as normal.

I wholeheartedly agree with the sentiment above: that everyone is an artist, but not everyone is afforded the opportunity for that artist to express themselves because of the way our for-profit society operates. And I don’t mean to make this all “it’s capitalism’s fault,” but really, this is capitalism’s fault. When we are spread so thin that all we have time for is ensuring our survival, there is no room for exploration and creation. The body remains in a heightened state of self-preservation: hyper-vigilant, on guard, and perpetually exhausted, leaving us mentally, emotionally, and physically depleted.

In last week's letter, I discussed how freeing my new retail job has been. My mental load has been significantly less heavy, and my husband and I have noticed a marked difference in my mood and creativity. This job has helped immensely, and I’m grateful for it—but even this is a double-edged sword. While my brain has more mental space for new ideas and explorations, my days now have new time constraints bound by shifts and commutes.

I haven’t worked in retail since I was about 25, so I’ve spent the last week or so reacclimatizing to a social sales environment. I forgot how it felt—especially for an introvert—to make small talk and foster connections with strangers to make a sale. And when I say foster connection, I truly mean it. I sincerely try to make everyone who walks through the door feel seen and heard. It’s an entirely different pace and speed and a welcome difference. I signed up for this, after all. But it is still exhausting, although in a different way. Most nights I come home hungry and tired after spending most of the day on my feet, with little time left to unwind properly before bed. Writing feels like the furthest thing from my mind when I walk through the door. I am happier; I have more ideas and creativity but have less time. It’s very The Gift of the Magi, which is seasonally appropriate.

As a woman, thankless work feels encoded in my DNA—even giving life is called going into labor. And it’s primarily women who pay after giving birth: in time, energy, and caregiving. Joan didn’t have to get a seasonal retail job between writing screenplays and articles for Vogue, and she was resourced enough to hire other women to support her with child-rearing. Her hands were significantly more free—literally and metaphorically—from the binds of both capitalism and motherhood, enabling her to have a prolific career, writing several of my favorite novels and short stories. Most of us are in the trenches, juggling unimaginable work and responsibility, and only if we’re lucky, some kind of creative practice. To those of you continuing to do this work, I salute you. I sincerely hope you keep going.

I recently tasked ChatGPT with creating my schedule for the next two weeks, inputting dates and deadlines, only for it to forget something crucial every single time. Eventually, I gave up and made it myself. The very same thing happened to my mother just weeks before but I didn’t believe her, so I tried it for myself. Even the thinking machines find our workloads unsustainable—they can hardly fathom it.

The writing comes because it has to. Like Didion, I write to keep my fears at bay, to examine them closely, hold them in my periphery, and make sense of my human experiences. Writing feels less like something I do and more like sustenance. It’s almost biological. But I do not have the luxury of a daily routine dedicated to my craft. My schedule has too many variables—things are constantly in motion. And a woman is always expected to bend, contort, and pander to everyone but herself.

I wrote this not to whine or diminish Didion’s brilliance but to humanize her—and all of us, in a way. She was incredibly flawed, as most of us are. I also wrote this to console myself. My free subscriber count dwindles every time I hit publish. I don’t have the capacity to publish at the cadence I’d like to for “growth,” but this cancerous growth mentality is not sustainable for anyone, and it’s certainly not possible for me right now. Whenever I think this way, I remind myself that most successful writers have scaffolding to help them get to where they are, and I do not.

Instead of feeling bad about myself, I can reframe: I am not talentless. My writing and words are valuable and meaningful. Success, whatever that vague and ever-changing word means, may come in time. But it will not come instantly or exponentially. What’s important is that I continue to do it anyway, creating that sacred time for myself despite the world’s blaring message that I don’t deserve it. Love is for the ones who love the work.2

I recently deactivated my TikTok, thank God.

For the Student Who Used AI to Write His Paper by Joseph Fasano.

Kait this is phenomenal, I was nodding my head the entire time I read

I loved reading this piece! thank you for sharing your words, insights and drawing these raw comparisons that us creatives face in today's complicated systems.