We are dancing animals.

"How beautiful it is to get up and go do something."

My love of the mundane is how I became creative. Once you notice that beauty lives everywhere, you move from one moment to the next in a near-constant state of wonder. Some strange experience becomes a song. A flower from your walk is a poem. Light slips through trees and bathes your room in dappled, honey-colored light, and you’re just a goner. You have no choice but to immortalize the moment with your craft, building a small world where others might experience some of the same magic. This is also why I read—I want to see what others see, understand what others understand.

To me, creation is an endless journey of opening oneself to the world. This process often requires us to go outside and do marginally uncomfortable things, like making small talk or meeting a tight deadline—activities that gently push you against a growth edge and urge you to evolve. Perhaps this is why Julia Cameron’s book The Artist’s Way is so successful: it provides its readers with a straightforward recipe for clearing the mind, getting out of the house, and seeing things in a way that stimulates the imagination. In this way, one becomes a conduit for creativity.

Last week, I started a seasonal job at a stationary store. I can’t help but notice that my work there doesn’t weigh on me like my previous modes of work once did, and this is a welcome change. The commute is slightly further than I’d like, but I’ve enjoyed the pace and shape my life has taken. I thought I knew what I was getting into when I accepted this position, but I never once considered it might actually improve my quality of life. What I initially saw as a chore has become more than just transactional or a means to an end—and while it certainly is both of those things, it’s also given me a deeper understanding of myself.

2020 ushered in an era of remote jobs. Until recently, I considered remote work the ultimate goal. Working from home relieved my introverted nature of the frivolity of office politics, tedious commutes, and sad desk lunches—all of which I had no patience for. I also knew that I never wanted to feel how I felt at my previous jobs: stuck, unwanted, and utterly miserable. But in avoiding these dynamics, I mistook dysfunctional office environments as the sole source of my woes instead of acknowledging that the real issue was the jobs themselves.

I wasn’t a fit for about 90% of the roles or companies I worked at before, and I don’t thrive sitting at a desk day after day, answering emails and posting on Instagram for brands and businesses. This is, in my humble opinion, the lowest expression of my capability and potential as a human being. I didn’t realize this at the time, and so for several more years, I kept trying to fit a square peg (me) into a round hole (jobs that weren’t right for me), each time retreating guiltily to the drawing board in the wake of what I thought were failures.

I never once considered that the answer to my problems might be returning to on-site work, but being in the world has proven to be an essential part of my creative process. I keep a pocket-sized notebook with me at work, jotting notes and ideas when the foot traffic recedes. Perhaps it sounds dramatic, but simply asking a stranger, "How are you?"—smiling, making eye contact, and expressing genuine warmth—has done far more to prepare me for my future career as a therapist than sitting at a desk, sending emails, or posting on social media ever could.

This temporary job is exactly what I needed. It shook up my routine and got me out of my head. I often make self-deprecating jokes about my retail experience, noting that my time at American Apparel lasted far longer than any jobs that followed—but it’s true. It remains the longest job I’ve ever held, probably because I enjoyed and was good at it. I liked the people I worked with; the stakes were low, and I could clock out at the end of my shift without taking any of it home. When I was off, my only work-related thoughts were about when I had to show up next. I didn’t need to design an email, think about a marketing strategy, or build a social media plan—all tasks that lived solely in my mind and became incredibly draining over time. My years at American Apparel were some of my most creative and prolific. I took risks, made things, and shared them without hesitation because I had more time and mental space to consider my own creative pursuits. It took me years to even consider that connection.

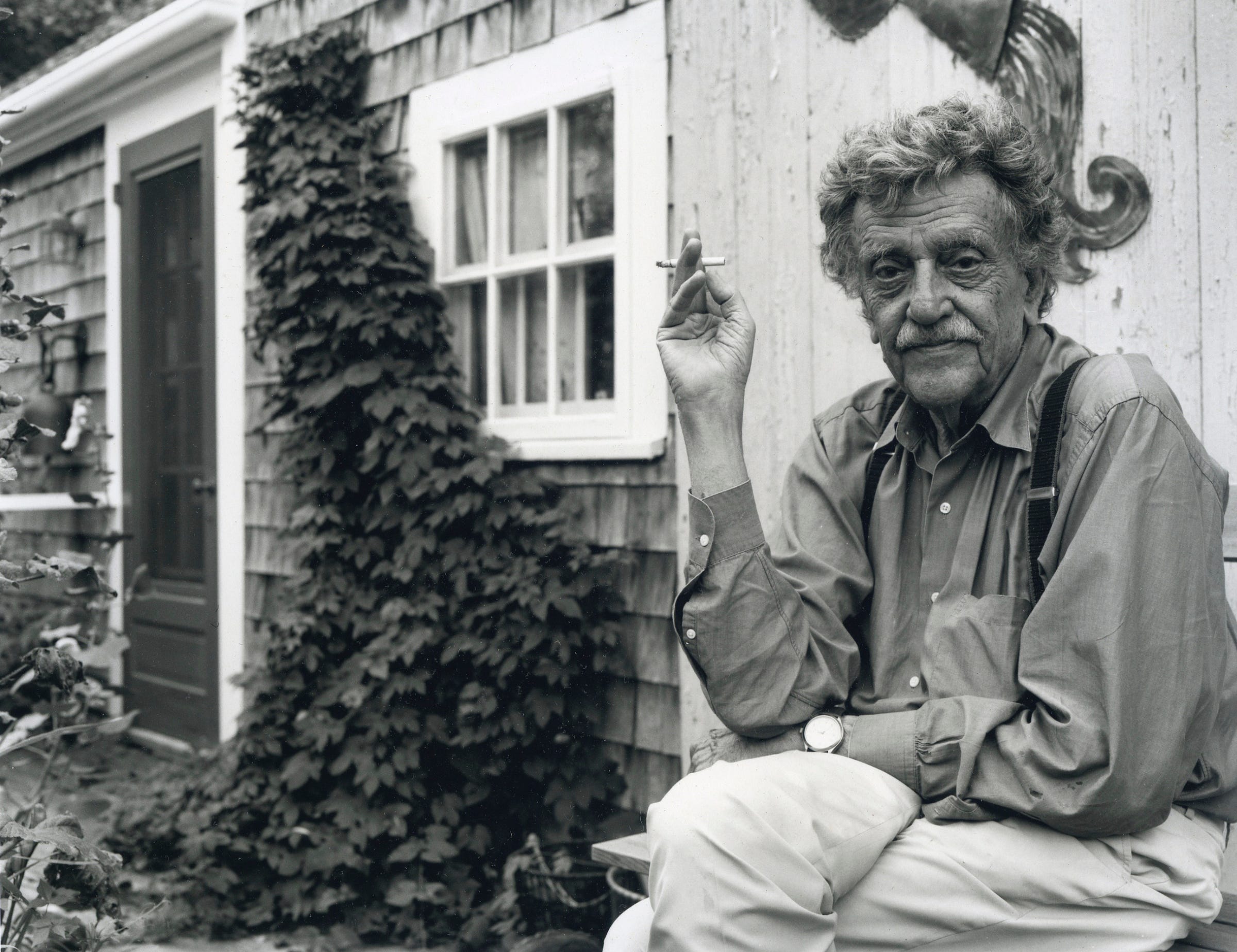

I love this Kurt Vonnegut quote (above) about the importance of being out in the world. His exact words are “fart around,” but the sentiment remains. Vonnegut’s practice of farting around undoubtedly contributed to his prolific writing career. You could order a thousand envelopes online, as his wife suggests, but doing so deprives you of all the experiences you have along the way—the experiences that fuel your creations.

As you check out, the cashier might remind you of your best friend from grade school, which makes you remember a mortifying experience from the sixth grade. And isn’t it strange how something similar happened just the other day? A baby smiles at you and you’re lost thinking about why babies bring people so much joy. This extended web of thoughts becomes raw material for a story, a painting, a film.

I’ve always loved this quote, and I reference it often, but what I never noticed before was the sentence that comes after it:

“Electronic communities build nothing. You wind up with nothing. We’re dancing animals. How beautiful it is to get up and go do something. [Gets up and dances a jig.]”

We take so much of our daily minutiae for granted. I know I did. Paying attention to how you feel in these moments—becoming viscerally aware of what’s around you, how you move through the world, how you interact with others, and the thoughts that arise from these experiences—enriches you both as a human being and as a creative person. You don’t get that when you work from home, have your takeout delivered to your doorstep, or order office supplies from Amazon. We’re living in a pivotal cultural moment, one in which people are beginning to recognize that constant digital noise is a major source of the pain and disconnection we face every day. The apps we once used to foster connections have slowly replaced them, diluting and flattening what were once rich and dimensional lives.

Our world likes to place more value on impressive, shiny titles, discouraging what people call “unskilled” labor. There’s a stigma around it, and I felt some of that at Thanksgiving when I told my extended family about my seasonal job. I saw confusion cloud their expressions as they tried to work out why someone who graduated with honors from UCLA would deliberately choose this kind of work. But the term “unskilled” is a misnomer. Connecting with people, being present, and showing genuine care are all incredibly valuable skills—not just for being a therapist but for being human. Based on our current sociopolitical climate, it’s painfully clear that not everyone understands how to develop those skills—or cares to learn. It has become a true rarity to feel seen and heard by others without the constant pings, chimes, and chirps of our devices. Undivided attention has become the new luxury commodity.

This digital landscape was sculpted and fueled by dreams of efficiency, individualism, and profit—ideals prioritizing a mechanical and automated way of moving through the world, devaluing human characteristics that make life worth living—knowing your neighbors, discovering a brick-and-mortar shop on your block, picking up groceries from your local market, or stopping into a nearby bookstore and nodding at the curmudgeonly shopkeep before perusing the shelves. We’ve forgotten how valuable these interactions are, but we are slowly remembering. Our bodies remember how good it feels to be in a community with other members of our species. It is a deep, ancestral knowledge that existed long before Meta and X and Amazon and will continue to exist long after.

Returning to the world of retail was initially a source of shame for me. It felt like going backward at first, but I now understand how important it was that I chose this. Without this experience, I may have continued for years wondering why I was so unhappy in all of my career pursuits. I may have even chosen to exclusively work in telehealth as a therapist, the result of which might have led me to surmise that I was yet again in the wrong field. All along, I was in the incorrect environment. I was a goldfish in a birdcage. It suddenly feels hilarious that I, an earth sign, tried to live for so long in an exclusively virtual landscape when experience, tactility, and connection are so essential to my well-being. The two-dimensionality of my virtual life seeped into my creative expression, making me feel stuck, dissatisfied, and isolated. Life imitates art, but art also imitates life. My art was nonexistent. I hardly made anything for several years because you cannot create something from nothing. You need source material to pull from in all acts of creation. My creative cup was never quite filled enough to do that.

Isolation as the source of human suffering is not a revolutionary thought, but it bears repeating. Alfred Adler was a doctor and psychotherapist who founded the theoretical frameworks of individual psychology, emphasizing the importance of a sense of belonging within our relationships and communities. Many therapists use Adlerian concepts without realizing it because his theories became so essential and pervasive within the field, much like those of Freud and Jung. We talk about him less though, because the answer is far less mysterious and interesting, whereas the drives and unconscious thoughts that fueled Freud and Jung’s ideas feel more intriguing and complex. The source of most of our problems, according to Adler, comes from isolation. If he were alive today, I can only imagine what he’d say about the repercussions of our brave new digital world.

Creation and connection are acts of defiance for which no virtual substitute exists. Electronic communities build nothing. You wind up with nothing.

We must be willing to look up from our devices and join the dance.

Stunning

Lovely post! I like that remote work is a way of working nowadays. It is important for us introverts to understand it isn’t necessary to force that extrovert side out all the time. It’s nice to be yourself and work at the same time.