Proust in the Age of Optimization

Escaping the Goodreads Industrial Complex.

I’ve been reading Swann’s Way since the beginning of 2025. It’s a profoundly uncomfortable pace for me. I am an overachieving academic who has maladaptively tied my self-worth to how much I read and how much I know. Moving at this pace makes me feel like the entire world is passing me by, and I have begun to feel the itch of literary FOMO as each new tantalizing title rolls out. Another one to add to my towering TBR pile. Working through that tendency as someone with one foot in the mental health field has been equally exasperating and illuminating. I’ve learned a lot, arguably too much, about where I tie my worth and how I value time.

I’m still reading Swann’s Way. And as the world rushes past me, I sit and read a handful of pages at a time when space forms around my work and school assignments. It’s difficult. I probably should have waited to read it when I was under less pressure and could luxuriate in the beauty of the writing. I thoroughly enjoy it, but I probably would have absorbed more if I were more… regulated. That’s the point of Proust, I think: to lose yourself in the words. To get lost in the beauty of the prose, forget your sense of time and space as early afternoon light slants into late afternoon. Proust has a way of slowing down time that our current world is at odds with. It’s a fascinating dynamic, one that feels similar to why people enjoy psychedelics. Your brain slows, but the world around you doesn’t. Not that I’ve ever done hardcore psychedelics; I’m far too anxious—just a harmless therapeutic psilocybin microdose here and there. I’ll stick to literature instead.

Our world doesn’t really allow us to get lost like that, and so we must be intentional with how we carve out our time. I declared that 2025 was my year of classics, and it seems many others are also dedicating themselves to a similar cause.1 Haley Larson, who writes Closely Reading, has created a whole book club and community of close readings of the classics. And you can easily type Middlemarch into your search bar on Substack and scan through the results teeming with mentions (and memes) of the hefty tome. We are all sidling up against the mysterious draw of books that hail from bygone times. I yearn for stories that aren’t peppered with mentions of the internet or smartphones. Stories that delve deeper into the quality of the human soul and its connection to other souls, and tell cautionary tales of hubris as forms of protest and rebellion. Several books written in recent years have done this. I’m not so pretentious as to ascertain that everything written in modern times is shit, but they remain the minority of what is published. Literary fiction, after all, only makes up about 1-2% of the market, a statistic that feels staggeringly low. I’m hopeful there will be a shift as AI dominates more of the written content, especially online. This will become a new form of social currency, a brilliant observation posed by Ochuko Akpovbovbo in a post I can unfortunately no longer find, but she quotes in this one.

Modern culture has an obsession with numbers. Profit margins, reading goals, calories burnt, miles covered, words written—numbers dominate everything. And I slowly began to notice that hyper-fixating on these numbers was sucking the joy out of everything I did. I went on a run a few weeks ago and started hating every second of it only five minutes in. Why? Because I was too focused on how slow my pace was, how much time I spent running, the miles I covered. This preoccupation with quantity made it miserable. Instead of enjoying it for what it was—moving my body, being outside, feeling the sunshine—I drank a cocktail of shame that poisoned the entire experience.

When I was in high school, I was personally victimized by the MyFitnessPal app (we should be entitled to compensation), which forced me to categorize and calculate the caloric value of everything I ate, exacerbating my already significant body dysmorphia as my young, easily-influenced mind and habits began to shift toward a disordered eating pattern and concerning preoccupation with weight gain. Around the same time, I started using Goodreads, a friendly-looking app that promised to keep track of all the books I’ve read and wanted to read, taking book discovery to an entirely new level. I promptly categorized all the books I read, marking them as either good or bad with little in-between, which I now realize aided in obliterating the possibility for nuance and meaningful discussion. I now refer to this dichotomous concept of categorization as the Goodreads Industrial Complex.

The common denominator among everything I’ve recounted is the constant quantification of what brought me joy and the consequential misery this quantification caused. I used to be able to run six miles at once, but now I hate running because I saw how few calories were burnt on shorter runs, and pushing myself to my limits every time I stepped foot outside became too exhausting. I misjudged books because I felt forced to rate them between 1-5 stars. And we all know that food becomes infinitely less enjoyable when you must constantly consider the caloric amount of everything on your plate.

Psychology was long considered a pseudoscience because its results aren’t easily and readily quantifiable. Mood disorders continue to be pinned under the microscope, with therapy-averse critics claiming these disorders are fictitious because they do, in fact, live in our heads. But whether or not something resides in our minds doesn’t immediately make it real or not real. Are your thoughts real? Let’s do some mental gymnastics around that for a second. On second thought, let’s not. I will spiral.

CBT and DBT, both excellent theoretical frameworks used to bend and shape human behavior, have become the norm within the clinical field because progress is easily quantifiable and, therefore, justified to insurance companies. But research shows that 95% of the success of therapy lies within the therapeutic alliance. That lives in our heads, too. Is that real? Seems pretty real to me.

Our lives are constantly measured, counted, and defined by numbers and objectives—hard data, “real” results. But most fail to recognize that the vast majority of the beauty of life, innovation, and creativity happens in between, when we force ourselves to think beyond the binary and explore the murky depths of a gray-area. Numbers and quantities are undoubtedly necessary. We want correct medicinal dosages and portions for our food. Even in creativity—committing to writing 1000 words daily is how you get to the good stuff. But our happiness and enjoyment begin to wane when it becomes too restricted or regimental. Always Be Optimizing culture isn’t really for me. Maybe I’m not supposed to be doing as much as possible, making sure I don’t waste a single second. I could drag my feet a little. Maybe that’s all part of the fun.

I won’t make the sweeping claim that social media introduced us to the concept of quantifying our lives because many things have contributed to that, and I think capitalism is the chief culprit. But social media’s introduction to the minutiae of daily life certainly didn’t help. In early days of the apps, we used them to socialize with friends and post pictures of our pets or breakfasts. Very wholesome and sweet. Now we collect likes, followers, and social clout via vanity metrics, tie entire livelihoods to it in some cases, which has (for me, at least) sucked all the joy out of whatever initially drew me to them. Forced to contend with my subscriber count that teetered between 275-290 for about four weeks straight last month, I was demoralized and disheartened by the writing process, stalling me and making me reluctant to write at all. Substack almost became a numbers game for me too, but I thankfully snapped myself out of that.

It’s difficult to slow down and be intentional when your life is as chaotic as mine is right now. Internships and punishing courseloads leave little room for a mind to wander. Even when I am idle, I am never not doing something: mentally outlining an essay, thinking about this week’s groceries, making note of the prescriptions I need to pick up from the pharmacy. But I try very hard to slow down time whenever I can. Proust has helped immensely. Has it taken me four weeks to read a single book? Yes. Does that even matter? No, it does not. Nobody cares except the mean, fictitious voice in my head—which, in this case, is not real, and therefore I do not have to listen to it.

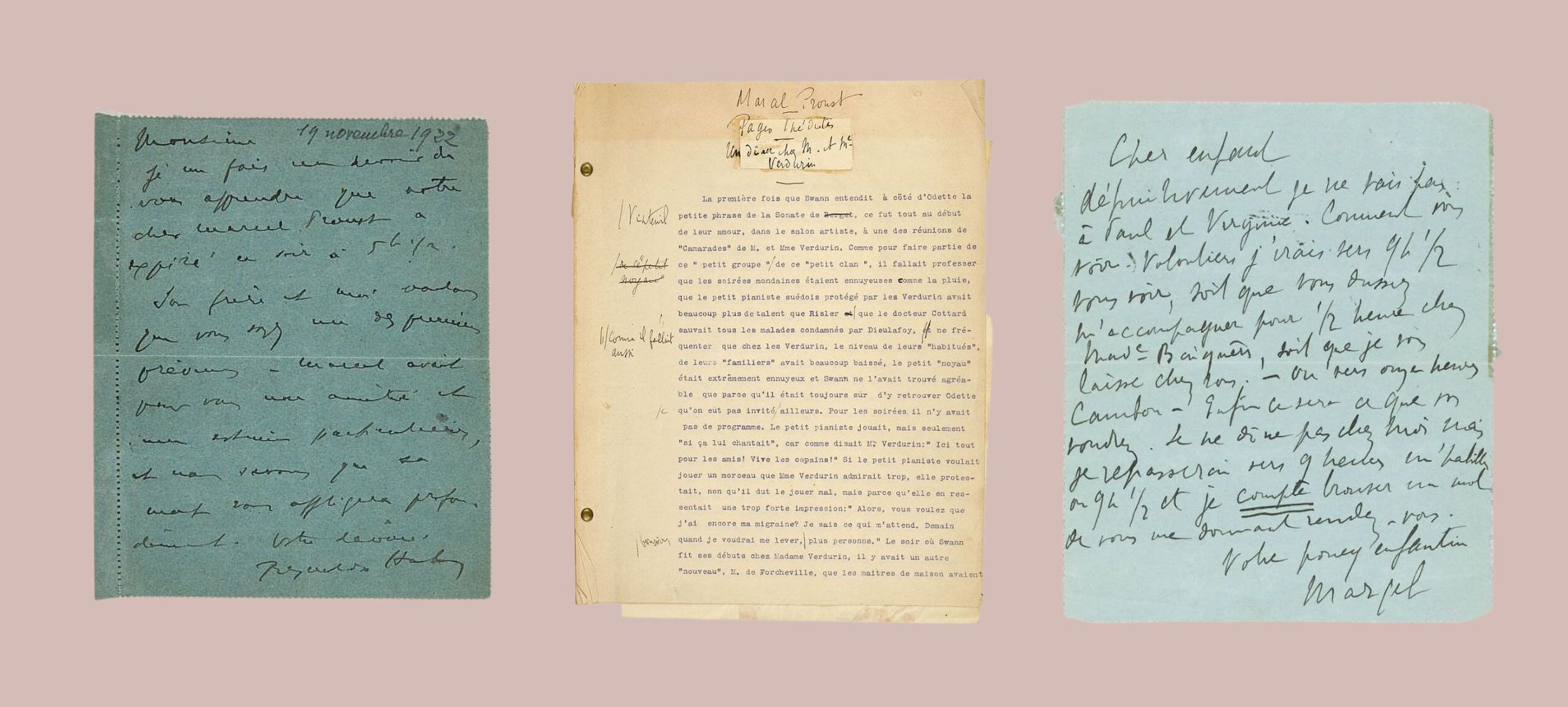

Aside from being a wonderful exercise in the art of slowness, committing to thoroughly reading the classics has made me a noticeably better writer. I counted several extra-long, comma-laden sentences in my last few posts, something I feel I owe to Marcel himself. But I still have not read Scaffolding by Lauren Elkin, or Blue Sisters by Coco Mellors. I have yet to lose myself in Didion & Babitz, despite them all sitting prettily on my bedside table, each title imploring me to crack them open and devour them like a pistachio nut.

I’ll get to them, all in good time. I’m in no rush. Sometimes, the moments leading up to the thing—all anticipation and excitement—is the best part.

As soon as I typed this sentence, I thought of Michael Scott declaring bankruptcy.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this, and it felt especially serendipitous to have done so on the first day of my new “deliberate, and slow” morning schedule.

Beautiful post Kait! I related in so so many ways, thank you for sharing x