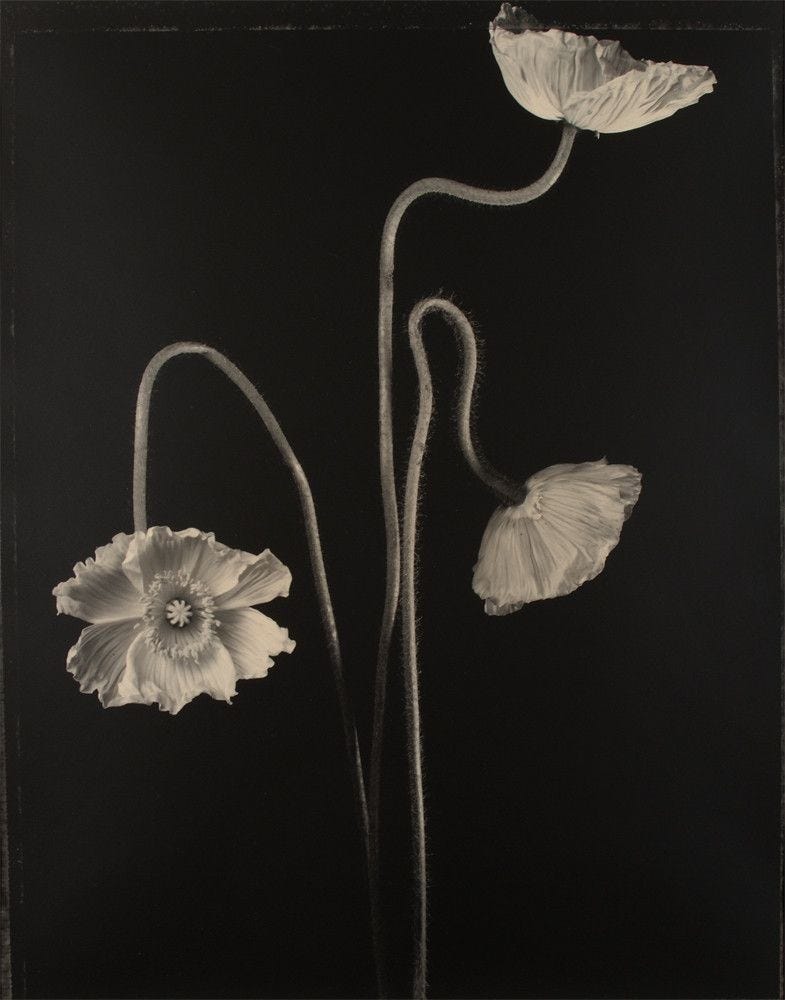

How the light gets in.

culture, constraint, and flourishing in an increasingly dystopian age.

This essay will most likely be truncated if you are currently reading it from your email. Read the non-truncated version via your web browser, or on the Substack app.

On the long drive toward Yosemite for our annual lake trip with friends, my husband and I listened to an episode of the Blindboy Podcast. It’s an enduring favorite of ours, most likely due to the meandering deep-dive structure of the episodes, which mirrors the switchback-like pathways of my own brain. Blindboy narrates it softly in his thick Irish accent, waxing poetic while musically punctuating every other sentence with the word “cunt,” which adds levity and charm to otherwise dense topics like religion, psychology, and myth.

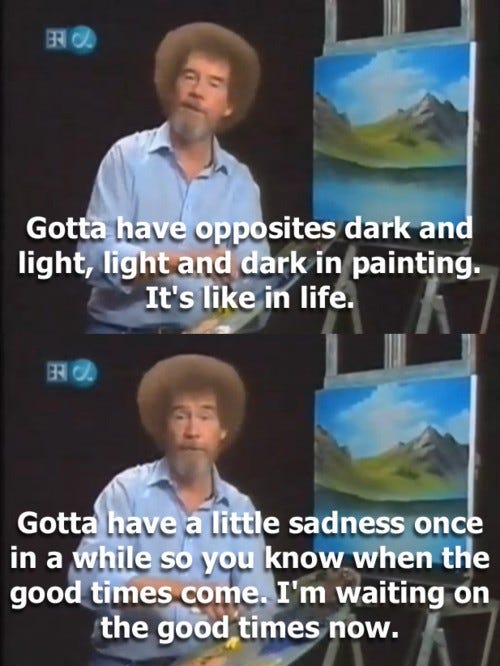

The episode we listened to discussed how Black Sabbath’s sound was shaped by the industrial accident that took the tips of guitarist Tony Iommi’s ring and pinky fingers when he was just seventeen. Those missing digits forced Iommi to adapt his guitar-playing style, contributing heavily to the dark, sludgy riffs that became Sabbath’s trademark. Blindboy compared this adaptation to Queens of the Stone Age, who similarly had to adapt their sound, not due to finger loss but due to the echoing landscape of the Sonoran Desert where Josh Homme grew up. In the band’s early days, any attempts to cover the classics were foiled by the dry desert earth because sound ricocheted against the landscape and made it nearly impossible for them to keep time. This adaptation was made for practical reasons, but it contributed to the synthesis of the band’s signature sound, later referred to as “stoner” or “desert” rock.

Just the week prior, I read a Stanford study from 20141 about schizophrenia. It discussed how those diagnosed outside of the U.S. experience psychosis differently from how it is experienced here in the States. In India, the participants reported benign and familiar voices, some of which spoke to them kindly. In parts of Africa, what we often jump to pathologize as “psychosis” is considered mystical, like hearing the voice of God. Participants from America, however, reported violent and threatening auditory hallucinations that spoke of terrifying things, profoundly disturbing those affected. These voices are fueled by paranoia and a pervasive sense that someone or something is out to get them, hence the now outdated term paranoid schizophrenic. The study revealed that not one person from America experienced a benign, familiar, or kind voice in their auditory hallucinations — not a single one.

On the surface, these anecdotes have little to do with one another; but they reveal something important about how influential a person’s surroundings are to their development. I couldn’t understand why people weren’t screaming from the rooftops about the Stanford study or why it wasn’t considered a health crisis here in the States, because this was clearly proof enough that something about our culture was undeniably wrong. The vast majority of us living in the States already knew that, of course, but this was tangible proof. It felt like the kind of discovery that could be a catalyst for new social and health policies — policies that would prioritize people over profit.

America is fraught with an almost pathological sense of individualism. We are taught that accepting help is a weakness, and that community and altruism are flawed, zero-sum games that lead to laziness and deceit (e.g. the accusations rooted in harmful stereotypes many conservatives enjoy hurling at the recipients of welfare or unemployment insurance). We are told that what benefits the collective means less for the individual, and so we have learned reject opportunities that create a more just and secure society, even when we have the statistics to prove that democratic-socialist paradigms (like those of Denmark or Finland) lead to healthier, more productive, and happier citizens2. Alas, we want that fleeting chance at becoming billionaires, even if that chance is a scant 0.000032%.

To grow up amid this culture means that selfishness, the me-versus-them mentality, is engrained within us in one way or another. When you consider that, it’s no wonder so many people supported the current administration. It’s not surprising that we don’t care about providing free school lunches, or student debt relief, or free health care. It’s no wonder our foreign policy hinges on exclusionary tactics rooted in xenophobia that enforce the false hierarchy positioning America as the greatest country there ever was. Most American citizens don’t want their tax dollars paying for someone else’s hungry child to eat, and they don’t want to pay for someone else’s “poor health decisions,” let alone provide aid to foreign countries, some of which are experiencing the cruelest forms of violence and mass suffering we’ve witnessed in our lifetimes. Not my problem, Americans say. I understand why people think this way from a sociological and psychological perspective, because the only way we can dismantle this kind of binary thinking is to understand it backward and forward. I don’t agree with it, but when you are raised with the belief that you are the most important, that as long as you are fine nothing else matters, what other outcome could we have possibly expected?

This made me think about the exceptions to the rule. Not all Americans adhere to this mentality. I certainly don’t, and I wondered if this has something to do with my neurodivergence. It’s common among those on the spectrum to have a strong sense of social justice and moral clarity. In fact, a recent fMRI study3 found that autistic participants were far more likely to refuse personal financial gain if it meant supporting a bad cause, regardless of whether anyone was watching. Neurotypical participants, on the other hand, often chose the immoral, self-benefiting option when they believed their decision was private, and only shifted to the moral choice when observed by others, less out of principle than out of fear of condemnation and ostracization. In other words, the moral consistency that comes with autism spectrum disorder is typically not performative. It isn’t contingent on surveillance, but rooted in a deep, internal code.

From a Narrative perspective, we are shaped in one way or another by the dominant narrative of the culture we live within. My desire for something greater, a collective, a support network, was born from my experience of living in a culture that feels like a wasteland devoid of community and mutual aid. We have no social support here, no safety nets, nothing keeping us from falling into the depths of debt and financial ruin in America, and we are all so much closer to the edge than we realize, caught within the vice-like grip of corporate greed and exploitation. My sociopolitical views were shaped by growing up in this country, which inevitably shapes my work as a training clinician. My ability to grasp this phenomenology of seeing the world through the perspective of another is second nature to me, so much so that I thought it was a capacity everyone had. But this was blind optimism on my part, and it became abundantly clear how mistaken I was in 2016 during that first hellish term that set the stage for all that was to come in the next decade.

But just like Tony Iommi, I have learned to live with what I do not have. This is where Fellini thrived, how Godard and Truffaut’s French New Wave came to be. How modernist movements like arte povera and dadaism emerged. How water pie, a depression-era confection4 made primarily of water, found its way into the cultural zeitgeist. It’s why African women braided seeds and rice5 into their hair during the transatlantic slave trade to feed their children and preserve their culture. Human beings have been tested and forced to do without for as long as history has been recorded, and still we find ways to continue.

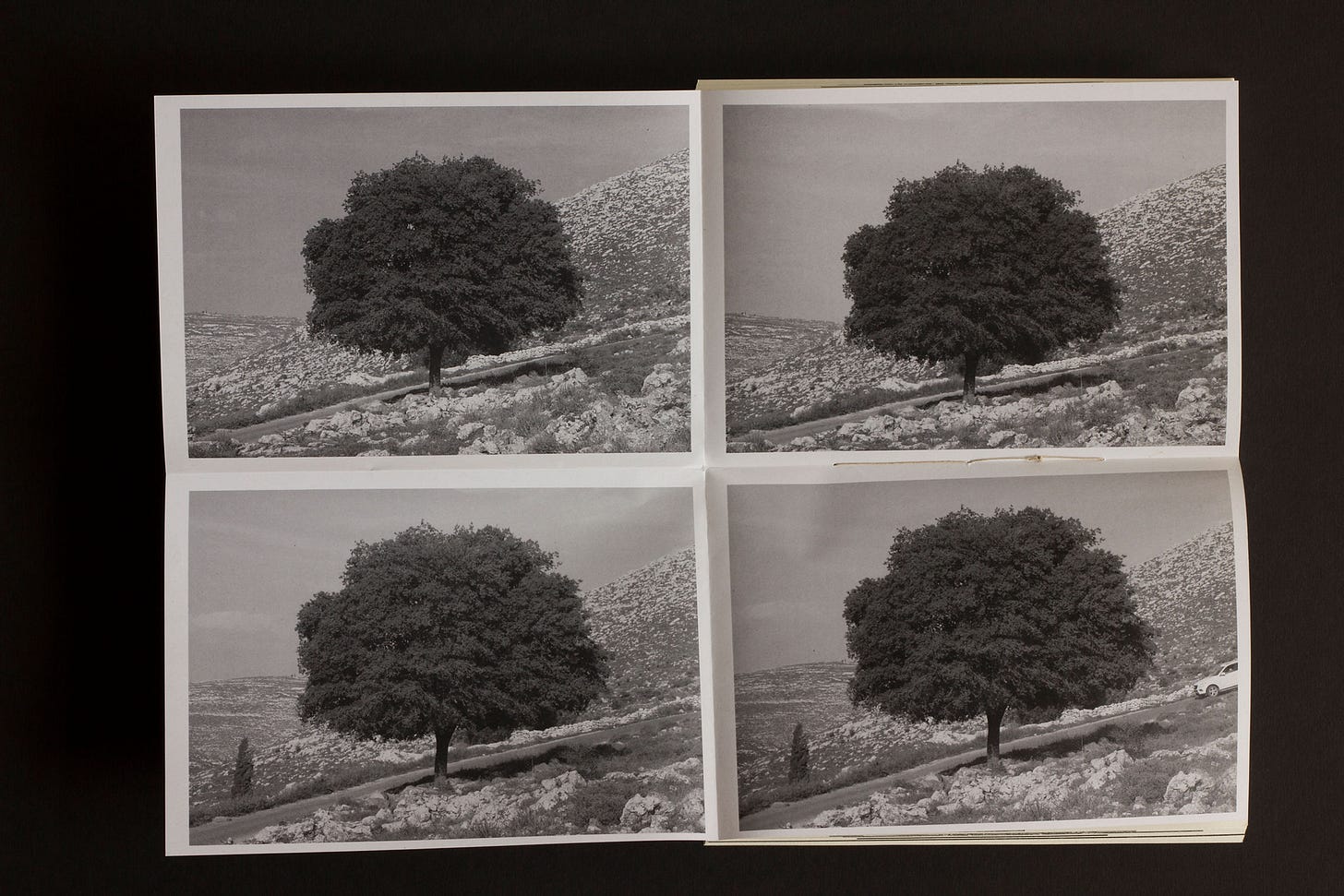

Each of us has what is called an actualizing tendency, an innate desire to thrive and grow toward the light, to continue even when conditions do not allow us to. And while I desperately wish we did not have to do without, that we lived in a society that provided us with all we needed to flourish, I find a devastating beauty within this tendency. Humans, despite all odds, have an incredible capacity for resilience. Humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers developed his theories around resilience and human potential after remembering his discovery of a potato sprouting in his basement during his childhood. The dark, damp environment was not conducive to growth, but the sprouts found a crack of light in the wall and grew toward it despite the unforgiving circumstances of its surroundings:

“The sprouts were, in their bizarre, futile growth, a sort of desperate expression of the directional tendency I have been describing … under the most adverse circumstances, they were striving to become. Life would not give up, even if it could not flourish … The clue to understanding their behaviour is that they are striving, in the only ways that they perceive as available to them, to move toward growth, toward becoming … the results may seem bizarre and futile, but they are life’s desperate attempt to become itself.” — Carl Rogers

Most of the generations following Gen X have not been set up for success. I turned thirty-two yesterday and have no savings, barely an income, and more student debt than I can fathom. My husband and I got married last year by the skin of our teeth, relying predominantly on family and friends to help us pull it all off. It was wonderful, and I’m so grateful we could have that experience. But we have no plans for a family or home ownership anytime soon. It isn’t possible right now because we live in a country that doesn’t believe in distributive justice. It’s every man for themselves here, and I am so profoundly tired of being told the lie that if I just work harder, stretch myself further, and sacrifice more, everything will fall into place. I don’t think I am alone in feeling that much of what we were promised in life feels put on hold, and it's difficult to find hope and motivation amid such dark times of political tumult and despair.

And despite all of this, somehow, I still have hope. As dark as the world gets, I cannot help but continue to hope, and it is an instinctual, almost feral kind. Perhaps that is just my innate human capacity for growth and resilience, my own little bizarre sprouts reaching outward and upward toward the light, toward something greater for all of humankind. I witness small and dazzling moments of hope and beauty every single day. I see it every time I sit with clients at my internship. I see it in my friends, my siblings, my parents, my grandparents. I see it in my husband and my dogs. I see it in nature, in literature, in art. Hope comes in variable shapes, and we can find it if we know how to look for it. It is a muscle. It is the mortar that holds our days together and gives us the strength to live through the present.

The loss of Tony Iommi’s fingers gave us metal as we know it. Poverty was transmuted into freedom, rebellion, and immediacy through handheld 16mm cameras in France, giving birth to French New Wave; and when fascism left Rome in ruins, Fellini built his black and white world of beauty against a backdrop of despair. The poor and displaced sailors and prostitutes of 19th century Portugal birthed the yawning arc of saudade in the form of the fado, an expressive style of music from Bairro Alto which comes from the word fate. The heartbreaking hymns of spirituals and Blues were born from the grief and devastation of slavery and colonization, alchemizing into jazz, soul, rock and roll, and altering music’s trajectory forever. I don’t recount these in an effort to excuse suffering. Every morning I wake up and wish it didn’t have to be this way, that there was more I could do to change things, because so much of it is the result of man’s hubris and so much pain throughout history could have been prevented. And yet the kind of cultural praxis I’ve described above is impossible without constraint. At least, if we must suffer, we can create something beautiful that future generations may look back upon and say: look what they endured, everything they created. They continued. Maybe we can, too.

Our instinct to reach toward the light is the only certainty history has given us: that out of destruction, grief, hunger, and ruin, we continue to grow. What comes of it may look strange, much like the tiny white shoots that Rogers describes, but it is always a form of becoming. It is what neurologist, psychologist, philosopher, and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl refers to as man’s endless search for meaning — the force that keeps us moving forward, filled with the vibrancy that comes from an innate desire to live. The story doesn’t end with the tragedy. It transmutes, giving way to something larger and more spectacular.

I have complicated feelings regarding organized religion, particularly as it is increasingly wielded as an instrument of oppression. I tend to hover somewhere between agnostic theism and atheism; even at my most skeptical, the absurdity and hopelessness of atheism has always felt too final. Writer, philosopher, and mystic Simone Weil saw suffering itself as the crucible of faith. What Carl Rogers saw in the pale potato sprouts in his basement, Weil calls grace: the mysterious force that fills the hollow spaces carved by affliction. Constraint, loss, and devastation prepare us, making us permeable to hope. But the void must come first.

“Grace fills empty spaces, but it can only enter where there is a void to receive it, and it is grace itself which makes this void,” Weil writes.

That’s how the light gets in.6

https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2014/07/voices-culture-luhrmann-071614

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cr72xep44kdo

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8115877/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_pie

https://geog.ucla.edu/sites/default/files/users/carney/33.pdf

Quote from the song Anthem by Leonard Cohen.