How to be invisible.

Healing the ever-present fear of being seen.

I have 72 drafts on Substack. I sifted through them a few weeks ago and realized there are some pretty decent pieces here that never saw the light of day because I was too afraid to publish them. I’ve wanted to talk about the witch wound for a while now, and I feel this is the perfect moment to do so. I began writing this early last year and it has since been revised to reflect current events.

I have hidden for as long as I can remember. In classrooms, I avoided the eyes of my teachers and professors, instead looking down at my hands in my lap, terrified I would be called on and inevitably make a fool of myself in front of my peers. This behavior seeped into social situations, manifesting in a deep-rooted fear of unstudied speech. I was afraid that if I revealed too much, I would be singled out and promptly discarded. I carried this behavior into adulthood and lived behind a series of masks, shape shifting until I no longer recognized myself. I still carry this with me. And still, I am untangling it. Showing up as yourself in a world that rewards homogeneity exposes you to the risk of being othered. Being othered is terrifying, and there are centuries of historical data that point to why that is.

The witch wound, a psycho-spiritual theory that people still carry trauma from the sixteenth century when witchcraft was punishable by death, is potentially one of these data points. I want to highlight the limitations of this theory — it has very white, Eurocentric roots. But this wound is present across cultures as most, if not all, have their own forms of witchcraft, from Santeria to Brujeria to Voodoo. The persecution of witches, however, is deeply rooted in colonialism and the policing of marginalized bodies, particularly those of women or those who do not identify as white cis-het men. Silvia Federici, author of Caliban and the Witch, wrote in depth about the through-line that carried us from feudalism into capitalism, how it contributed to the witch hunts of the sixteenth century and beyond, and was weaponized to reinforce the ridiculous notion that women were inferior, as was all the free labor they did that kept daily life conveniently humming along.

What’s less focused on when learning about the witch trials is that most of those accused of witchcraft didn’t practice any witchcraft at all. Everyone accused had at least one of the following characteristics in common: wealth, poverty, knowledge, power, beauty, or were elderly. It isn’t mere dramatization in The Crucible, the finger pointing and blaming, the jealousy and hatred. John Proctor screaming, Give me my name! Overwhelmingly, this persecution was the ammunition used to codify the puritanical ideals of misogyny and oppression that would go on to shape much of American society and culture today. But many men were also persecuted for standing up for the women accused. Mothers, wives, sisters, aunts — they all had husbands, sons, brothers, nephews. Each “witch” had families that were entangled in the accusation, marking anyone who chose to speak out as an accomplice. This subconsciously taught anyone who witnessed their plight that speaking up was unsafe. It wasn’t the first time this dynamic was present in history, and it certainly wasn’t the last.

What I find most difficult to accept about this is that thousands of women and men were sentenced to death simply because they had something someone else either wanted or feared. I find this difficult to accept not because I don’t believe it, but because of the sheer ludicrousness of it all. Roughly 40,000-60,000 people were sentenced to death for witchcraft in Europe between the 15th and 18th centuries. The Salem Witch Trials paled in comparison, with 200 accused, thirty sentenced, and nineteen people killed by hanging. Some inherited properties from fathers or husbands, or had a wealth of knowledge about herbalism, midwifery, or simply knew how to read. Others too loudly and freely spoke their minds, whistleblew, outed abusers, and others found that threatening. Some were simply beautiful, which caused those around them to spiral into jealousy and spite. And some were impoverished, old, or isolated, as was the case of poor Lilias Adie in Scotland, whom I think about often. None of the cases had any tangible evidence, of course. It all hinged on eyewitness accounts and word of mouth. And the “trials” often consisted of double-bind situations like fixing weights to the accused and throwing them in a body of water to see if they’d sink. If they sunk, they weren’t a witch, but still died by drowning. If they didn’t sink, they were a witch, and would then be hung.

The silence of those around them, the bystander effect, became a learned affectation, the only response for safety in these situations. Psychologically, it is a form of dissociation. It’s the only way our bodies know how to proceed when confronted with such horrors, our minds unable to comprehend them and still continue on with our lives. When your thinking mind is overidden by fear, and you react instead of respond. Witnessing tragedy and oppression on this level perpetuated the notion that it was unsafe to do anything that drew too much attention to oneself. In the case of the witch hunts, it was unsafe to know too much, to have too little or too much money, to be pretty, or to simply age. During the Holocaust, it was speaking up for your neighbors as they were ripped from their homes and sent to concentration camps. Presently, it takes the shape of remaining silent as ICE invades your town and makes people disappear. This is how generational and ancestral trauma takes root. These are the seeds that hold the potential to breed more cruelty and hate if unresolved.

Whether or not this tendency actually can be traced back to the witch wound, its existence functions like myth, carrying cautionary tales of what happens when hubris prevails. In this case, it warns us of what happens when we ignore our inner voices, teaching us to tamp down our intuitive gifts and talents because of this pervasive fear. I see how these themes take root within my own life: my deep, ancestral fear of being seen, of choosing to write in depth about tarot, of using my voice for activism. I will continue to do it all, but I am terrified all the time.

Those who embody this wound are often people-pleasers and self-erasers who do everything they can to appease those around them at the expense of themselves. They grow up learning to be hyper-vigilant and fearful of attention because, subconsciously, there is a fear that this ultimately leads to persecution and death. They internalize the belief that in order to stay safe, they must remain silent and away from the watchful eye of anyone who might be offended by their existence. And I won’t refute this internalized belief, either. Much of it is rooted in lived experience, or witnessed experience. Queer and trans folks, Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people, women, and so many other marginalized groups — they all have very valid reasons for their fear of being seen, and I want to make that abundantly clear.

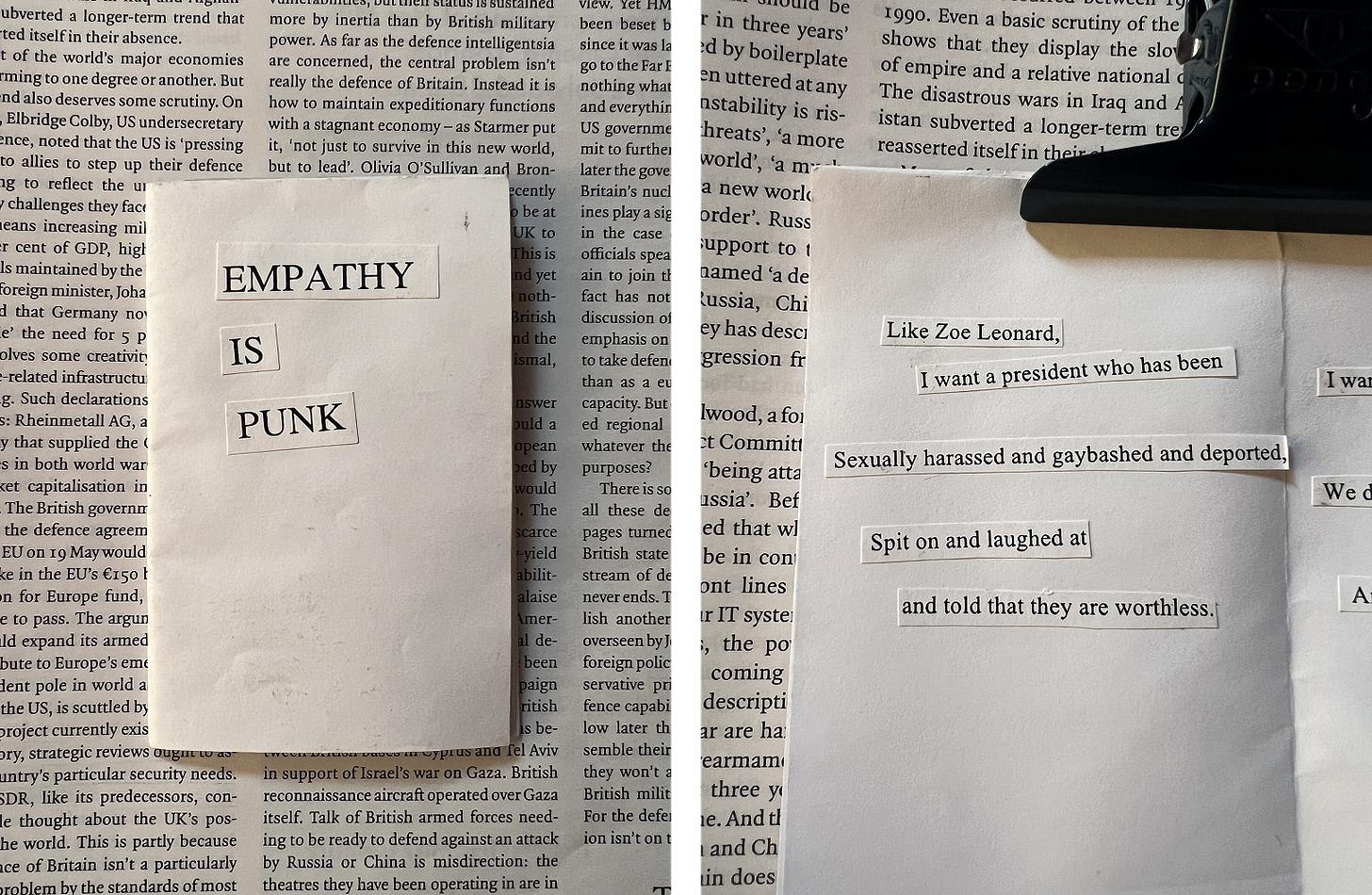

In college, an excellent professor called me out for hiding. At the end of the course, we had one-on-one critiques for our final projects. My final project was a zine called “EMPATHY IS PUNK,” a sentiment I still stand by. I was proud of it, because it was the first time I allowed myself to be publicly angry. To risk being seen in a way I had never been seen before. This professor told me, point blank, that I need to stop hiding. He was kind about it, but it was a wake-up call. When I followed this thread, I began to see its presence throughout my life. I minimized myself constantly, was anonymous, overly modest, afraid of my own potential, ashamed of my anger. I spent most of my life waiting for permission to exist and be myself.

I wish I could say that, following that advice from my professor, I lived my life without fear, but I didn’t. I wrestle with this fear every day, and our current administration has only amplified it. Sometimes, this fear wins. Showing up on social media, posting videos speaking to the camera — every fiber of my being wants to wipe myself from the internet and never be perceived again. Part of this is due to my secretive nature (I am very Hermit-coded, and I am a Scorpio rising, after all). But another part is due to a very valid fear of exposure, and I am not nearly as vulnerable as other identities in America currently. I understand the enormity of my privilege, and still I am scared. Every day, a new legislative measure is passed that violently polices marginalized groups, makes people “illegal,” and strips us of our basic human rights. If they’re willing to write that into law, there’s no telling what they’re willing to do behind closed doors. We’ve seen what people are capable of, the cruelty and hatred that runs rampant, and outright nazis are given platforms to spew their hatred. All of that unfolds in plain sight.

Now, at thirty-one years old, I am stepping back into the realms of play and magic and curiosity. I am still terrified, but aware of all at risk if I don’t unapologetically be myself. I don’t know what tomorrow will look like. I don’t know what next month or next year or the next decade will hold. At our current rate, history will continue to repeat itself, and we could very well see our own modernized version of the witch hunts. One could even say we’re in the midst of one right now, with many fearful of voicing dissent and losing their citizenship.

I suppose this is my own personalized way of conceptualizing the term YOLO. We do, indeed, only live once. And unfortunately our one wild and precious life is taking place concurrently with the rise of fascism. It would be tragic not to have sucked the marrow from life while I had the chance. I am not saying we’re doomed, that we must do everything we can in a frenzy before it’s all over. I am saying that nothing is guaranteed. Not tomorrow, not next week, not our health, or our freedom. And so it becomes an essential act of resistance to continue showing up as yourself, and not what society has deemed acceptable. Being seen, witnessed, perceived in any form will always require some risk, just as any act of creativity requires the creator to accept that failure is a possibility every time they make something.

I understand the fear because I pay attention. Because I read and understand history and see patterns in everything. Centuries of tragedies have consolidated this fear. It is woven into our DNA, influencing our thought processes and shaping our very lives. But we can be terrified and still continue. One of the prevailing reasons why those on the wrong side of history are so full of hate and rage is because we aren’t giving up and admitting defeat. Women have not ceased calling out abuse, assault, misogyny. LGBTQIA+ folx are not going back into the closet or obscuring parts of their identities. Black, Latinx, Indigenous, and AAPI folx have not stopped calling out the pervasive structural racism and bigotry that scaffolds American policy. And the allies fighting alongside all of them have not fallen prey to the temporary sense of ease that complicity falsely promises. The refusal to be invisible is one of the most powerful tools we have at our disposal right now. It is in our best interest to use it.

Thank you for sharing this Kait. I recently listened to a couple episodes of Myth Matters podcast about Psyche and Eros. In one of them, Dr. Catherine Svehla talks about how Psyche was literally exiled and sent away for being too beautiful, and how when listening to the story, it can bring up some pangs of where we feel "too-muchness" in our own lives. I definitely have been feeling those pangs, and reading this piece was a nice reminder that I am not at all alone in this. Thank you for showing up as your full self, and inspiring us to do the same despite the complexities of it all :)

Felt this so deeply, thank you for sharing Kait <3 and for continuing to create and put yourself out there despite the fear