Elements of Style: Anaïs Nin

The sublime, sensorial world of the controversial literary legend.

Elements of Style is, of course, a nod to the iconic writing manual by Strunk and White—a guide that champions clarity, concision, and the ruthless elimination of excess. In many ways, personal style is no different. Whether in writing, dress, or design, style is about distillation, paring something down to its most essential, intentional form. It becomes life’s scaffolding—a language, a mythology, a way of being. This series explores the visual and material worlds iconic figures have built around themselves and their art, examining how style extends beyond just fashion and offering a brief glimpse into the psyche of those who mastered the art of self-presentation.

Joan Didion famously understood the power of aesthetic control. From the sparse economy of her prose to the deliberately crafted image of the writer in dark sunglasses and a white Corvette Stingray, Didion’s style, both literary and visual, was an act of precision. She played what Lili Anolik, in Didion & Babitz, describes as a man’s game, idolizing Hemingway and wielding a clipped, surgical voice that held its own against the likes of Mailer, Capote, and Thompson. Her restraint was deliberate, her clarity a form of power.

Anaïs Nin, much like Babitz, leaned into excess. If Didion’s approach was a studied exercise in withholding, Nin’s was an indulgence in sensation. Whatever your opinions about her, there is no denying her predilection for beauty. She was a poster child for sensory-driven living, evident in both her writing and the lush, decadent dwelling she built in the hills of Los Angeles. While Didion weaponized restraint, Nin curated a mythology of eroticism, decadence, and dreamlike fluidity. But both, in their own ways, understood the performative nature of style and used it to shape their literary legacies.

Nin’s self-mythology was not without strategy. Like Didion, she played within the limitations of gender constructs to bolster her place in the literary world, though their methods diverged. Didion became the man, while Nin used the man to her advantage. She lived a life of deception, famously committing bigamy and remaining married to two men on opposite coasts for nearly a decade. Even her harshest critics can acknowledge that her bigamy became a defining scandal—one that, had she been a man, would likely have been praised rather than condemned.

Of course, Nin remains a contentious literary figure, lauded and vilified in equal measure. After learning more about her history, I now see her for what she was: a deeply traumatized and flawed individual who was never able to process her grief, leading to a pattern of self-destructive tendencies framed as hedonism. But to be human is to be deeply flawed, and her experience with despair led to the creation of some of her most beautiful and influential works. Her style—while enviable—was inevitably informed by all aspects of her history: her life, her trauma, her faults, and most importantly, her self-mythology.

A house like a velvet-lined jewel box.

Style is more than just aesthetics. We are long past the notion that an interest in fashion or design equates to frivolity. Style is an extension of the self, an immersive world one creates through the careful selection of clothing, artifacts, and curios for no other reason than because they bring a particular kind of pleasure. The way you dress, decorate your home, and move through the world is part of a dance between beauty and practicality. Nin’s life and work followed this same choreography. Her home and personal style weren’t just reflections of her artistic ethos; they were expressions of a worldview that prized beauty and pleasure above all else.

Her Silver Lake home embodied this philosophy—a space both opulent and intimate, where the drama of her life unfolded in jewel-toned rooms draped in velvet. I love the use of purple here—a hue that evokes mystery, femininity, and creativity, all prominent themes within her life. When I first encountered these photos, I was stunned. It was as if the dream home that had only existed in my mind had suddenly materialized. A space designed for both creative solitude and seduction, for writing and for hosting salons. Every detail—the candles, the incense, the draped fabrics—was a mise-en-scène for the theatricality of domestic life.

“Luxury is not a necessity to me, but beautiful and good things are.”

This belief in beauty as necessity rather than indulgence is one that I share. Nin made a distinction between material excess and true beauty, suggesting that beauty itself is not an indulgence but a fundamental ingredient of a life well-lived. There is a distinct influence of Parisian salons, Eastern mysticism, and surrealist sensibilities in her curation—a world of tastes and artifacts collected from her travels.

Dressing the part.

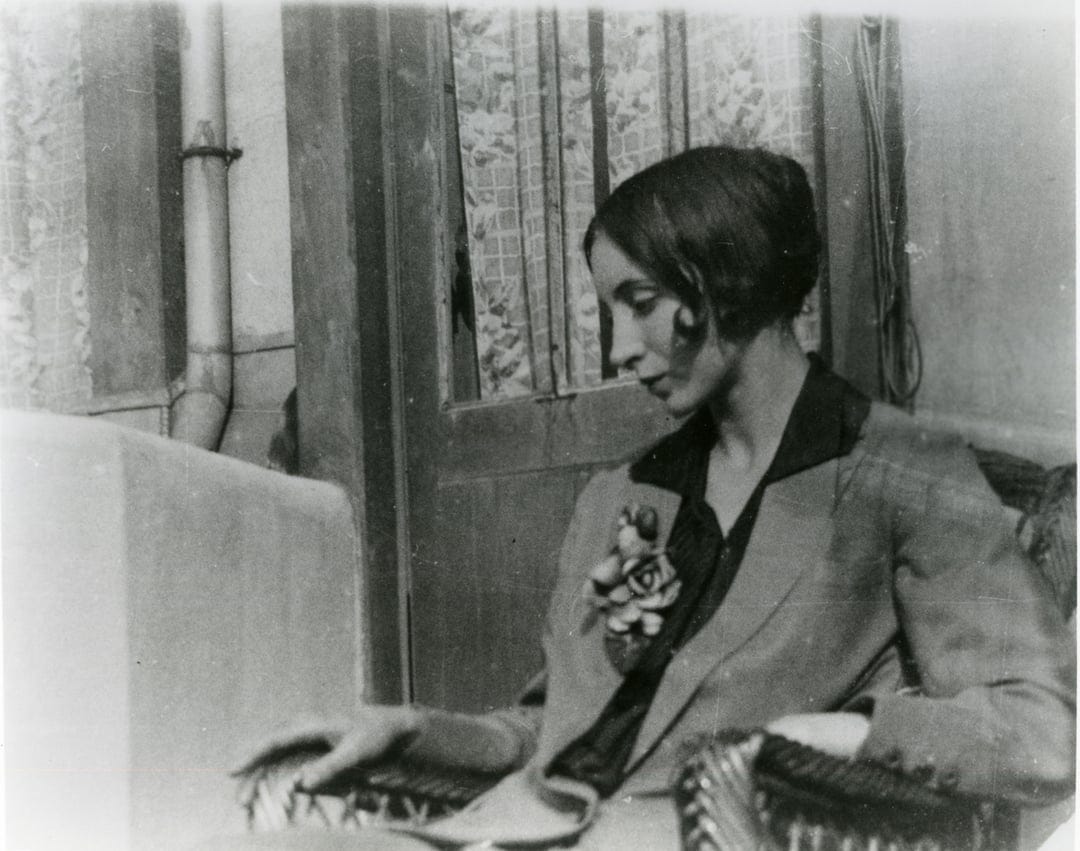

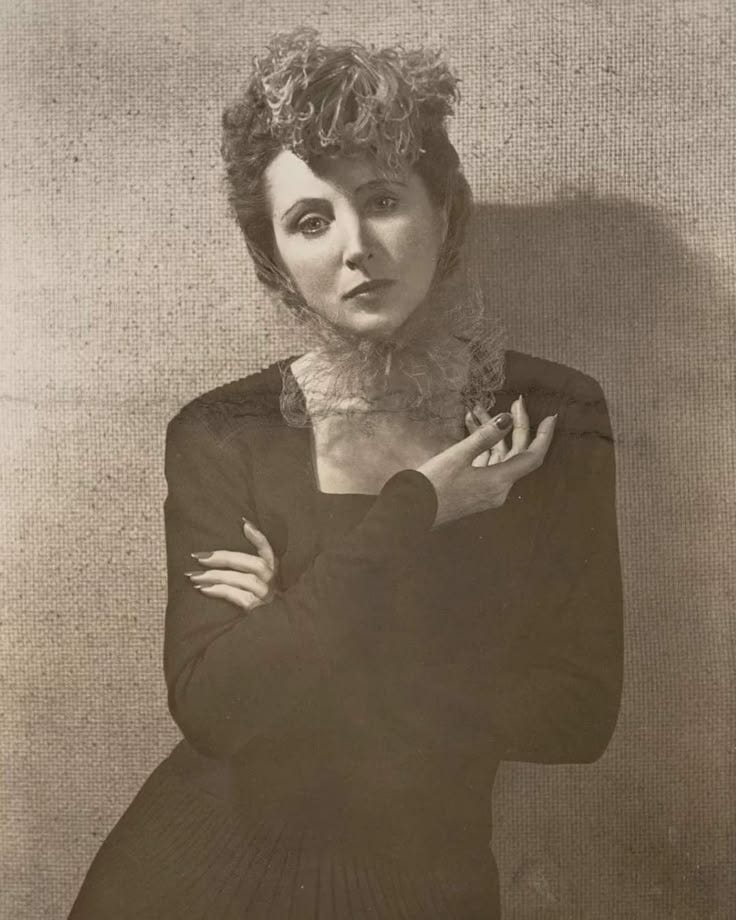

Her aesthetic sensibilities extended to her clothing, which functioned as another layer of self-mythology. Her wardrobe—silk robes, block-print textiles, intricate lace, deep jewel tones—is evident in every photo of her across the decades. In her youth, she embraced the opulence of the 1920s—silk brocade, velvet, and lace confections—later transitioning into the turtlenecks and richly patterned textiles of the 1960s. Her style, like her writing, was fluid, an evolving manifestation of her personal narrative.

Clothing, for Nin, was storytelling. Sensual, layered, evocative of the eras and cultures she inhabited, her aesthetic was curated at every level, not just for herself, but for those who entered her orbit. There was an intentionality in the way she balanced softness with intensity, ethereality with control. Her life and environment were a myth of her own meticulous making.

This feels like a stark contrast to a figure like Sylvia Plath, who was denied the ability to shape her own mythology. After her death, Ted Hughes carefully revised and controlled how she was presented to the world, conveniently leaving out any incriminating mentions of his affairs and abuse in Plath’s poetry and diaries, ultimately distorting her legacy for decades. Discovering the extent of Hughes’s role in shaping Plath’s posthumous reputation made me reconsider Nin’s self-mythologizing as something powerful rather than deceptive. She crafted her own narrative, refusing to let the world dictate how she would be remembered. It makes this quote all the more haunting:

“Had I not created my whole world, I would certainly have died in other people’s.”

Nin’s life and work were inseparable from her aesthetic sensibilities. Her surroundings, her clothing, even her handwriting fed into the mythology she scrupulously built around herself. Whether one sees her as an icon or an illusionist, her commitment to having autonomy over her reality was absolute. She understood what some might dismiss: that style, when taken seriously, is not frivolous. It is a language, a narrative, a reclamation—a way of bending reality to fit one’s vision. And while many writers, particularly women, have had their stories rewritten for them, Nin seized control of her own in many ways. Whether you see that as disingenuous, empowering, or both, one truth remains: few bent reality quite like Anaïs Nin.

Suggestions for further reading:

Delta of Venus: Erotica by Anais Nin • Henry and June • A Spy in the House of Love

I have a few names in mind for the next month’s feature, but I’m always open to suggestions. As always, thank you for being here and supporting my work. Every like, comment, restack, share, and paid subscription is meaningful, and it goes a long way in helping a writer continue doing work she loves. x

Anais Nin was a massive influence. Thank you for writing about her so beautifully.

Ok I hate to admit this, but I’ve never read anais nin! If you could recommend one book to start with, what would it be? Thank you!